Beyond the Suicide Study: The Quiet Suffering of Autistic Individuals and a New Path Forward

A Study Shines Light on Autism’s Silent Struggle

In 2025, a research team led by Tanatswa Chikaura uncovered a stark truth: autistic adults report far higher rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviorseven when they haven’t experienced trauma[1]. The study, published inAutism Research, surveyed 424 autistic adults (and 345 non-autistic peers) about dozens of negative life experiences — from bullying in childhood to lack of social support — and about their mental health.

The results were sobering.

Yes, traumadoesincrease the risk of self-harm and suicide in autism, just as it does for anyone[2]. But even after accounting for traumatic histories, autistic people were still much more likely to have seriously contemplated or attempted suicide[3].

In fact, being autisticitselfemerged as a significant risk factor for suicidality and psychological distress[3]. As Chikaura’s team concluded:

there seem to beunique aspects of autism— for example, sensory sensitivities or the constant effort some autistic individuals make to“camouflage”their differences — that contribute to this elevated risk[4].

What suicidal thinking reveals about autistic suffering

One statistic jumps out from the study:1 in 4 autistic adultshad attempted suicide in their lifetime[5].

Imagine a room of autistic people and realizing that a quarter of them have been in such despair that they tried to end their lives. It’s a chilling figure that sounds an alarm for anyone who cares about the autistic community.

But the implications of this study go even further.

It’s not just about preventing suicide; it’s about recognizing thequiet sufferingthat too many autistic people live with day to day, often out of sight.

The unseen majority: autistic people living in quiet suffering

For every autistic person at obvious risk of suicide, there are countless others in deep psychological pain who may never reach a crisis point that draws outside attention.

They are the ones who“live in quiet suffering,”enduring chronic anxiety, depression, or burnout that outsiders don’t see.

Research consistently finds extremely high rates of mental health challenges in autistic individuals. In one study, 71% of autistic youth had at least one diagnosed mental health disorder (often anxiety or OCD), and similarly high rates persist into adulthood[6].

By adulthood, depression and anxiety become the two most common psychiatric problems for autistic people[7].

This is thebaseline.A staggering proportion of autistic people who wake up every day to an internal battle with negative thoughts, fear, or sadness.

Camouflaging, masking, and the hidden cost of appearing “fine”

Even those who appear “high-functioning” or who mask their struggles well can be suffering profoundly inside.

Autistic adults often describe putting on an act —camouflagingtheir autism — to fit in socially. They might force themselves to make eye contact, hide their need to stim (self-soothing movements), or endure overwhelming situations without protest.

Research shows this camouflaging comes at a steep cost: it isstrongly linked to anxiety, depression, and even suicidal thoughts[8][9].

One systematic review found that autistic people who camouflage more have significantly worse mental health. Masking, as it’s called among the community, is essentially a risk factor for serious psychological problems[9].

They might seem fine to teachers, coworkers, or even family, but inside they are near a breaking point.

As one autistic adult described it, years of trying to appear “normal” and meet others’ expectations can lead to:

autistic burnout,a state of complete exhaustion and loss of abilities after being *“severely overtaxed by the strain of trying to live up to demands that are out of sync with our needs”[10].

It’s not hard to see how an autistic person could reach that point.

How sensory overwhelm fuels constant anxiety

Daily life for an autistic individual oftenismore stressful. The world can feel like an onslaught of unpredictable stimuli — loud noises, glaring lights, chaotic social interactions — that never let the person’s brain fully relax.

A recent study confirmed what many autistic people have been saying all along:sensory overwhelm can directly fuel anxiety.

In the study, 246 autistic adults were asked how their sensory sensitivities related to their anxiety levels.

The overwhelming response was that sensory hyper-reactivity (like extreme sensitivity to noise or touch)causestheir anxiety more than their anxiety causes sensory issues[11].

In other words, if you live with a sensory system that is constantly on high-alert (flinching at the slightest sound, feeling pain from a light touch , etc) you live in a near-constant state of tension.

One analysis put it succinctly:

“Sensory hyper-reactivity may cause anxiety due to autism-related difficulties with the unpredictability of aversive sensory input.”[12]

Small wonder that an autistic person might always seem “on edge”. Their worldisedgy and full of potential ambushes (a fire alarm, a scratchy sweater, the chaotic chatter of a cafeteria) that their brain flags as threats.

Social experiences can be just as punishing.

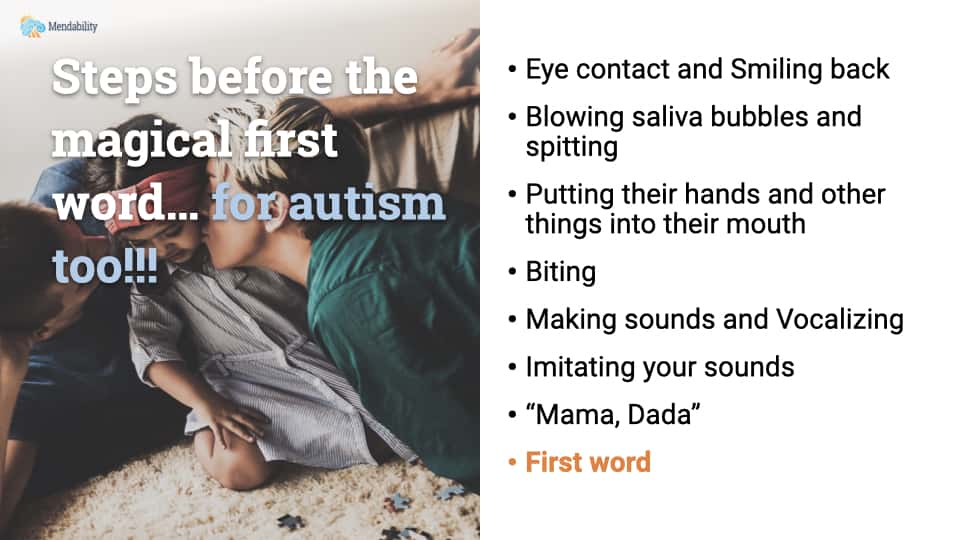

Ordinary moments that become trauma

Many autistic individuals have lived through bullying, exclusion, or repeated failures in environments not built for them.

By mid-life, themajorityof autistic people have experienced some form of interpersonal trauma.

It’s no surprise, then, that rates of PTSD symptoms in autism are dramatically higher than in the general population, estimated between 32% and 45% of autistic people haveprobablePTSD, versus around 4% in non-autistic groups[13].

What’s particularly heartbreaking is that autistic people can be traumatized by situations others might shrug off.

Dr. Freya Rumball, a psychologist and autism researcher, has found that her autistic clients often list“ordinary” events as traumatic: the death of a pet, a sudden change in routine, a sensory event like a loud fire alarm, or evenbeing prevented from doing a calming repetitive behavior (stimming)[14][15].

Think about that…

An autistic child might be traumatized by well-meaning adults constantly stopping them from flapping their hands or rocking (perhaps in an effort to make them look more “normal”).

The very coping mechanisms that help autistic people soothe themselves are sometimes stripped away, unintentionally leaving them defenseless against stress[15].

Physiologically, chronic stress takes its toll on the autistic brain and body.

When the stress system never gets to rest

Some studies have measured cortisol (the stress hormone) in autistic children and found abnormal patterns — some kids with autism havehigherbaseline cortisol or exaggerated stress responses, while others have a worn-out stress response.

One investigation even observed that when autistic individuals were exposed to a mild stressor, those who showed a bigger spike in cortisol also engaged in more repetitive self-stimulating behaviors[16].

The researchers interpreted this as those behaviors (hand flapping, rocking, etc.) beingstress responses,the person’s attempt to cope with or discharge the stress[16].

Now imagine a therapy or classroom where those stress-coping behaviors are forbidden because they look odd.

The person’s silent distress likely only amplifies. It’s a recipe for trauma that no one sees externally — until perhaps it erupts in a meltdown or a depressive collapse.

All of this paints a picture that goes far beyond suicide-related behaviors.

The broader crisis: not just suicidality, but chronic despair

Yes, preventing suicide is critical– every life saved is immeasurably precious.

But the real takeaway from Chikaura et al.’s study, and so many others, is that we as a society have been missing the broadercrisis: too many autistic people are living in pain.

They are anxious, overwhelmed, and hurting on a daily basis.

They may not be voicing it (some literally can’t put it into words, others have learned not to complain), but they desperately need relief.

When support unintentionally becomes harm

If autistic individuals are enduring chronic distress, one would hope that our therapeutic approaches and educational supportsreducethat burden, not add to it. Yet, in our rush to help autistic children “catch up” or fit in, we often fall into well-intentioned but dangerous traps.

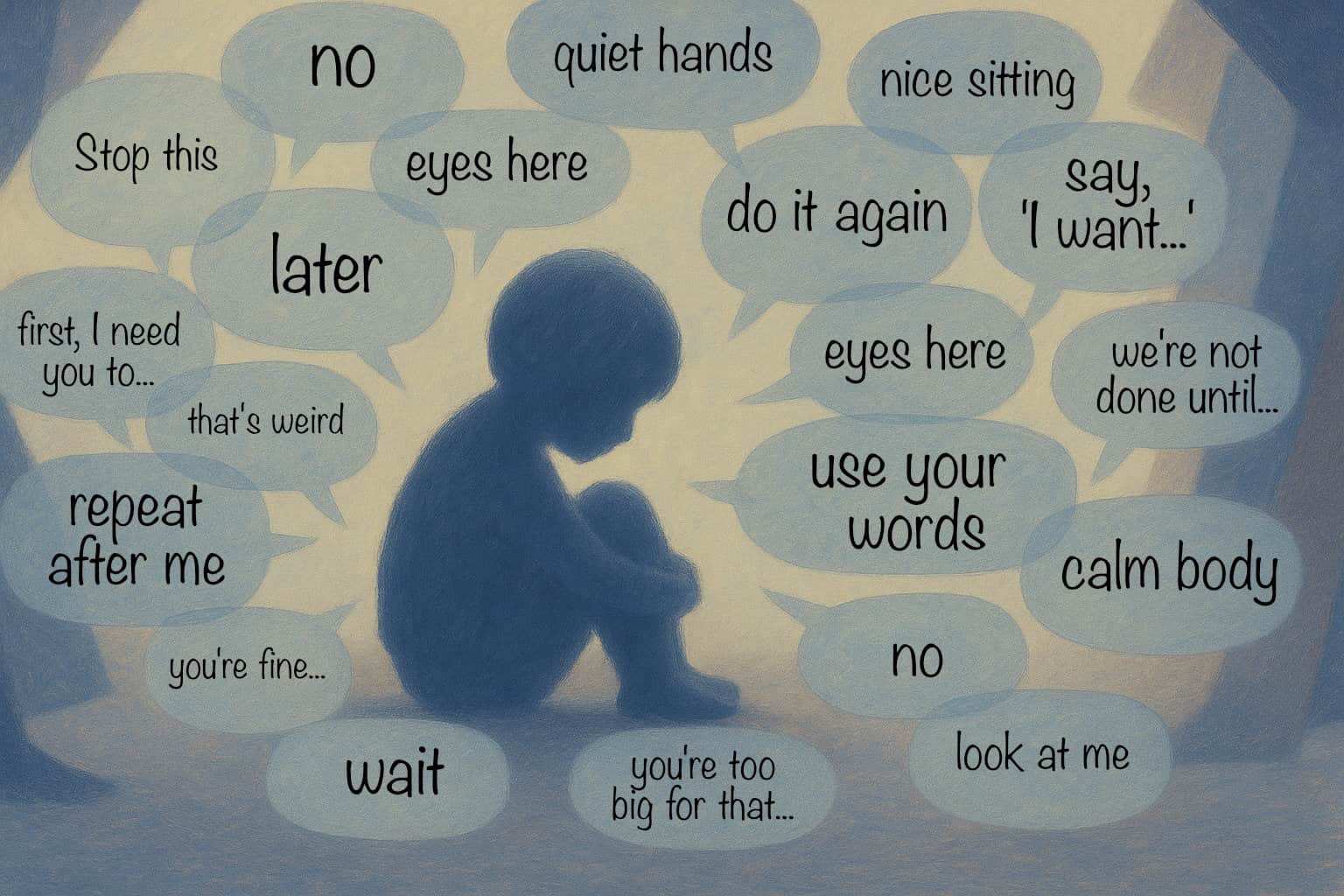

Why performance-based therapies can deepen long-term distress

Traditional autism therapies — especially those that areperformance-based or compliance-focused— can inadvertently compound an autistic person’s stress and trauma.

What do we mean by performance-based models?

These are approaches that prioritize outwardbehaviorsand skills above the person’s internal state. They often measure success by how well an autistic child conforms to neurotypical norms:Did he make eye contact? Did she sit still in class? How many words can he say now?

Goals like these aren’t inherently bad. Of course we want kids to communicate, learn, and participate.

The problem ishowwe go about achieving those goals.

Too often, it’s done through intense drills, rigid programs, or reward-and-punishment systems that push the child to perform without addressingwhythey’re struggling in the first place.

The pressure to perform: what children actually learn

An all-too-common scenario: a young autistic child is enrolled in hours upon hours of therapy each week, where they’re constantly prompted to do things that are extraordinarily difficult for them — touch this texture that you find aversive, comply immediately with every request, “use your words” when all you feel is panic.

If they resist or meltdown, the behavior is labeled as defiance or non-compliance to be extinguished.

The focus stays ongetting the right responsein the moment, rather than understanding the child’s feelings.

Over time, the child might learn to suppress their protest and comply, earning their rewards or praise.

To outsiders, it looks like progress. But inside, the child may be learning a harmful lesson:

My natural reactions are wrong. I must ignore my discomfort. If I want to be good, I have to pretend I’m okay.

This is exactly what the “Mendability Manifesto” warns against:“performance-based therapies that train children to mask their struggles, only to see them fall apart under real-world stress”[17]. Such approaches don’t just fail to provide true resilience —“they often cause lasting harm”by lowering the child’s self-esteem and teaching them to disregard their own needs[17].

Mistaking compliance for progress

Let’s consider a concrete example.

Recall how many autistic individuals find relief in stimming or need extra breaks due to sensory overload?

A compliance-driven program might aim to eliminate stimming (because it looks odd) and keep the child at the table for as long as possible to practice a skill. The therapist or teacher might constantly say, “Quiet hands!” or “Stay in your seat or no reward.”

The child complies, but their anxiety is mounting because they’re not getting the sensory regulation their body craves.

Eventually, that stress has to go somewhere. Maybe it comes out as an aggressive outburst at home, or self-injurious behavior, or simply in a growing internal conviction that everyday life is scary and overwhelming.

In the worst cases, years of this kind of pressure contribute to the individual breaking down entirely in adolescence or adulthood (the so-called autistic burnout).

What makes these mistakes especially tragic is that they come from a place of wanting to help.

The unseen injuries of well-meaning interventions

Parents and professionalsdothese things because they’ve been taught that intensive practice and behavior correction are the keys to “fixing” autism. But as the autistic adult community and progressive clinicians have been pointing out,when success is measured in compliance instead of joy, we are failing the person[18].

Pushing a child to act “normal”without addressing their underlying distressis a short-term fix that can lead to long-term damage.

The Mendability team puts it plainly:

“These approaches don’t just fail —they often cause lasting harm. They lower self-esteem and reinforce the belief that [the child is] only lovable or acceptable if they try harder, act differently, and stop being a burden… [They] teach unsuspecting children to ignore their needs, distrust their instincts, and internalize failure when the scripts fall apart.”[17]

Reading those words might sting, but they ring true.

So many autistic adults today report that as kids they got the message thatnothing they did was ever good enoughunless they were emulating a neurotypical kid.

That’s a recipe for trauma.

Four common anti-model mistakes to avoid

It’s time to recognize these well-meaning missteps for what they are. In fact, let’s call them out so we can avoid them going forward. Somecommon pitfalls in autism treatmentinclude:

·Outsider-Only Intervention:

Relying solely on therapists in a clinic, once a week, to “fix” the child, while families are sidelined. This often fails to generalize to real life and can make the child feel therapy is something donetothem, not supportedaroundthem[19].

·Focusing on Appearance Over Comfort:

Training children to“act ‘normal’”— make eye contact, sit quietly, stop stimming —instead ofaddressing why they feel uncomfortable or helping them self-regulate[18]. This swaps the symptom for the root cause.

·Measuring Success in Compliance:

If a program brags that a child is now “obedient” but the child is more anxious and withdrawn than before, is that really success? True success should be measured in confidence, happiness, and independence — not just in how well a child follows commands[18][20].

·Ignoring the Child’s Voice and Needs:

When a child’s reactions (crying, resistance, meltdown) are seen only as behaviors to eliminate, rather than communications to heed, the approach is likely doing harm. Children might “behave” in the short run out of fear or confusion, but their authentic self is being traumatized and silenced.

These pitfalls carry a heavy price: they can turn thesupporta child should receive into another source of stress and trauma.

We have to do better.

We need to flip the model on its head:support the person from the inside out, rather than trying to coerce external behavior change from the outside in[22].

A Gentler Way: Feel Better to Do Better

What might a better approach look like?

Imagine a model of care where the first priority is helping an autistic personfeel safe, calm, and comfortable in their own skin.

Instead of starting with“How can we get them to do X skill?”, we start with“How can we reduce their stress and meet their sensory and emotional needs so that learning and growth become possible?”

This is precisely the philosophy behindSensory Enrichment Therapy— a family-centered, sensory-based therapy model that stands in stark contrast to the traditional compliance-first mindset.

The origins of Sensory Enrichment Therapy are rooted in compassion.

It was developed byClaudie Gordon-Pomares, a clinician and mother, whose life journey shaped her conviction that we musthelp the person feel better first.

A childhood loss becomes a mission

As a child, Claudie had a best friend named Simon who had Down syndrome.

One day, Simon suddenly stopped coming to school.

When Claudie went to his house to find out why, she learned that Simon’s parents had sent him away to an institution — not because they wanted to, but because they felt they had no way to support his needs at home[23][24].

Claudie was heartbroken.

She saw firsthand what happens when families aren’t given the tools to help their neurodivergent children: those children end up isolated and everybody suffers.

She vowed to find a better way to help people like Simonwithoutbreaking their spirits or segregating them from family life.

From lab science to family life: the birth of Sensory Enrichment

Fast-forward to the 1990s: Claudie, now trained in neuroscience and psychology, began translating cutting-edge brain research into practical activities that parents and children could do together[25].

She had read studies showing that“environmental enrichment”— basically, providing animals with a richer, more stimulating, butlow-stressenvironment — led to remarkable brain changes, improving learning and memory even in older animals[26].

Claudie thought, why not try this with children? Instead of drilling kids on tasks, she designed playful“brain games”that paired sensory experiences in novel ways.

For example, a game might involve a parent and child gently touching textured fabrics while listening to certain sounds, or smelling a pleasant scent while doing simple stretches. These activities were short, fun, and engaging to the child’s senses —the goal was to spark the brain’s natural capacity to adapt and calm itself.

Claudie’s early trials of this approach in French daycares and hospitals were astonishing. Parents reported children sleeping better, being more attentive, andeven showing surges in developmental progress.

In one project, some infants with developmental delays made leaps that defied the typical timeline — “children who went from laying down to standing up and walking” without crawling, as Claudie recalled excitedly[27].

More profoundly, these babies and toddlers werehappier— they were alert, curious, and even demonstrating empathy in ways no one expected of a child that young[28].

It was as if reducing their internal friction (sensory discomfort, stress) unlocked their ability to do things that had been “stuck.”

Why sensory enrichment works: the neuroscience of safety

Sensory Enrichment Therapy (now the basis of theMendabilityprogram) doesn’t target speech, or motor skills, or behavior problems in isolation — it targets thefoundationupon which all those skills rest: the brain’s state of balance and receptivity.

As Mendability’s team puts it,

“Instead of working on specific symptoms directly, [we use] a stress-free approach… giving the brain what it needs to build real, lasting abilities”[29][30].

The therapy involves a customized set of sensory exercises parents do with their child each day, often as little games woven into daily routines (during bathtime, playtime, bedtime, etc.).

Crucially, these exercises areenjoyable— they are not chores or tests.

They might involve things like gentle touch, massage, smelling spices, listening to music, exploring tactile toys, all in combinations that research has found can promote neural growth.

The sessions are short (on the order of 10–15 minutes a day total) because the goal isquality of input, not quantity of pressure.

And the parent or caregiver is the one delivering it, meaning it happens in the context of a loving relationship — the child isn’t being taken to yet another stranger, but is connecting with someone they trust.

As one of the core principles of Sensory Enrichment Therapy states:

“a family that plays together heals together.”[31]

Does this gentler, comfort-first approach actually yield results beyond just a happier mood? The evidence says yes.

What the clinical trials actually showed

Multiple peer-reviewed studies, including randomized controlled trials, have tested sensory enrichment programs for autism, and the outcomes have been remarkable.

In the first randomized trial led by researchers at UC Irvine, children who received Sensory Enrichment Therapy for 6 months made6 times more improvementsin their autism evaluations than the control group receiving standard care[32].

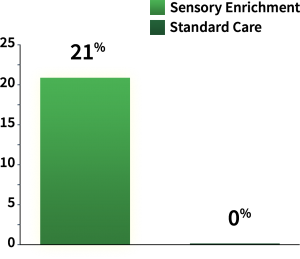

After six months, the percent of children who fell below the

autism cut-off score using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule

(ADOS). They found that 21% of the children who received sensorimotor

enrichment in addition to their standard care fell below that mark, while

none of the children receiving standard care alone reached that level of

improvement. Two-sample test for proportions, p = .01.

Parents reported gains in communication, social interaction, and reduced repetitive behaviors — and these weren’t just marginal gains. In a follow-up replication trial, an incredible21% of children in the enrichment group improved so much that theyno longer met the diagnostic criteria for autismafter six months, compared to 0% in the standard care group[33].

Yes, you read that correctly: some children went from meeting the clinical threshold for autism to falling below it — essentially, they caught up to a point that typical therapies almost never achieve in that timeframe. These children also showed an increase in IQ scores on average[32].

What’s even more encouraging is that improvements were seenacross a wide range of ages and severity levels— from toddlers to teenagers, from kids with mild Asperger’s to those with significant delays[34].

In other words, focusing on helping the brain feel safe and enriched benefited alltypes of brains.

How is this possible?

Why improved well-being unlocks real abilities

It comes down to stress and neuroplasticity.

When the brain is constantly in “fight or flight” mode — as it often is when an autistic person is overwhelmed or anxious — it simply does not learn or grow well. It’s busy just surviving.

But give that same brain a dose of safety, a novel but pleasant sensation, a moment of joy shared with a parent, and a fascinating thing happens: the brain’s chemistry shifts.

Reward neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin increase, stress hormones decrease, and suddenly the brain is in an optimal state to make new connections.

It’s like the soil has been watered and fertilized; now development can take root.

Mendability’s approach is essentially to till the soil and nurture it, rather than yanking on the plant and demanding it grow.

Over time, a less stressed brain can’t help but function better — mood improves, attention widens, and yes, skills and behaviors start to come along for the ride.

The role of relationships: why family-centered approaches outperform drills

One parent whose son went through Sensory Enrichment Therapy noted that not only was her child sleeping and learning better,shefelt more positive and patient simply because the household stress had come down[35][36].

When you have a calmer, happier child, the whole family benefits.

None of this is to say that teaching specific skills or behaviors is bad. The point is that those things stick bestafteryou’ve addressed the person’s comfort and emotional well-being.

As Mendability’s co-founder Kim Pomares often explains, their goal is to help children“overcome anxiety and other challenges to feel happier and more confident,”because from that state, real learning and independence can flourish[37].

Confidence and emotional resilience become the springboard for trying new things, whether it’s speaking, making a friend, or tolerating a busy classroom.

This stands in stark contrast to the compliance model where a child might be trained to do something but feels awful inside — eventually, that house of cards collapses.

The sensory-enrichment model is about building a sturdy foundation first.

Rethinking Care: From Pushing Performance to Nurturing the Whole Brain

The message for parents, caregivers, and professionals is clear and heartfelt:we must rethink how we approach autism care.

The science is telling us that if we truly want to help autistic individuals thrive, we need to start by alleviating their chronic distress, not by intensifying it.

We need to stop accidentally treating autistic behaviors as the “enemy” and recognize the real enemy is psychological suffering. An autistic person who feels secure, understood, and comfortable in their environment will naturally be more engaged and capable.

So our first job is to create that comfort and security.

To do this, we have to break some old habits and avoid the common mistakes of the past. Let’s stop chasing short-term wins like a few more vocabulary words or a perfectly quiet child in the grocery store, if achieving those wins comes at the cost of the child’s trust and joy.Instead, let’s chase long-term well-being and resilience.We can begin by making sure any intervention or therapy adheres to a simple litmus test:Does this make the individual feel safer and better, or not?A therapy session might be challenging (learning new things isn’t always easy), but it should never leave a child traumatized or defeated. As the Mendability Manifesto declares,“real progress happens when the brain is supported from within — not coerced from the outside”[22].That means building the person up through positive, enriching experiences, not tearing them down by constantly pointing out deficits.

How to support an autistic child without contributing to trauma

Practically speaking, caregivers can take several constructive steps right away:

·Prioritize Emotional Safety:

Before any learning task, ensure the environment is not overwhelming. This might mean using noise-cancelling headphones, allowing movement breaks, or starting sessions with a calming sensory activity. A brain that isn’t bracing for danger is free to learn[38][39].

·Follow the Person’s Lead:

Incorporate their interests and listen to their signals. If a child is getting upset or shutting down, respect that. Push just enough to challenge, but not so much that you trigger panic. Growth happens in the sweet spot between comfort and slight challenge — not in terror.

·Make Therapies Playful and Family-Centered:

The more therapy feels like a game or ordinary fun (hide-and-seek with scents, painting with textured materials, dancing to music), the more the child’s brain will engage without stress. And when family members join in, it stops being “work” and becomes quality time. A child who laughs with you is a child who will trust you when you introduce something new.

·Measure Success Differently:

Celebrate improvements in regulation, curiosity, and happiness. Maybe your son only learned one new word this month, but he started smiling more and had fewer meltdowns — that ishuge. Those are the gains that pave the way for more learning. By all means track academic or therapeutic goals, but place equal (if not greater) weight on the person’swell-beingindicators.

·Empower, Don’t Sideline, Caregivers:

Parents and close caregivers know and love the individual best. When they are equipped to be part of the therapeutic process, progress accelerates and the individual feels supported 24/7, not just in a clinic. No one should feel that therapy is some mysterious process only done by experts — it can and should happen through everyday nurturing interactions[19].

Perhaps most importantly, we need to remind ourselveswhywe are helping this person.

Why changing the brain is more powerful than correcting behavior

It’s not to make themseemnormal for the sake of society’s comfort.

It’s to enable them to live a fulfilling life on their own terms.

That means focusing on theirwhole-brain development and mental health, not just isolated behaviors.

When we approach care with a mindset of love and respect — aiming to soothe the person’s struggles and unlock their innate potential — incredible transformations are possible.

We have seen nonverbal children begin to speakaftertheir sensory issues were addressed and their anxiety lowered. We have seen teens on the verge of giving up rebound and find their path when given permission to be themselves and tools to manage stress. We have even seen some autistic individuals attain a level of independence that earlier seemed out of reach, because someone finally stopped forcing them to “perform” and instead helped their brain truly heal and grow.

The recent research by Chikaura et al. sounded the alarm:autistic people are in pain, far more than most of the world realized.

We cannot ignore that any longer. But we must respond to this alarm not with fear-based measures or doubling down on control, but withcompassionate, science-backed carethat addresses the root causes of that pain.

It’s time to move away from approaches that inadvertently scream to an autistic person “You are broken, you must change,” and instead embrace approaches that softly say “We are here to help your brain feel better, because we love you as you are.”

The shift from a performance paradigm to a“whole-brain”paradigm is not just a therapeutic change — it’s a moral one.

Replacing quiet suffering with quiet healing

Autistic individuals deserve to flourish, not just survive. And flourishing becomes possible when we ensure they feel safe, supported, and understood. The research, from neurobiology to psychology, is converging on this truth:a calm brain can focus and learn, a supported person can gain true independence[31][40]. By reducing chronic stress and honoring sensory needs, we set the stage for genuine progress that lasts a lifetime.

So let’s answer this call to action.

Avoid the common mistakes — and choose what protects, empowers, and heals

Let’s rethink our approach to autism care starting today. Whether you’re a parent, therapist, teacher, or doctor, you can choose to prioritize comfort over compliance, connection over correction, and resilience over rote performance. In doing so, you will not only help prevent the worst outcomes like burnout and suicide; you will also uplift the countless autistic individuals who have been quietly suffering for far too long.It’s time to replace the quiet suffering with quiet healing — and eventually, with joyful thriving.By healing the brain from within, we truly“free the person”to be themselves and to shine[41].

In the end, this is about love and hope.

Love demands we listen to what autistic people have been telling us about their inner lives. Hope is what we offer when we take their suffering seriously and choose a better way. The quiet suffering may have been invisible before, but it is invisible no longer. And now that we see it, we can all commit to easing it — gently, patiently, and wholeheartedly — until every autistic individual can live a life of safety, growth, and dignity.

Sources:

Chikaura, T. et al. (2025).Traumatic experiences, psychological distress and suicide-related behaviours in autistic adults.Autism Research.[1][4][3][5]

Hull, L. et al. (2021).Is social camouflaging associated with anxiety and depression in autistic adults?Molecular Autism, 12(1).[8][9][6]

Rumball, F. (2022). “Post-traumatic stress disorder in autistic people.”National Autistic Society.[13][15]

Raymaker, D. et al. (2020).Defining autistic burnout.(Summary via NAS)[10]

de Vaan, G. et al. (2020).Associations between cortisol stress levels and autism symptoms in people with sensory and intellectual disabilities.Frontiers in Education, 5:540387.[16]

Pineda, M. et al. (2022).Sensory reactivity differences and anxiety in autistic adults: Perceived causal relations.(via PMC)[11][12]

Woo, C.C. & Leon, M. (2013).Environmental enrichment as an effective treatment for autism: a randomized controlled trial.Behav. Neurosci.[42]

Woo, C.C. et al. (2015).Environmental enrichment therapy for autism: A clinical trial replication and extension.Behav. Neurosci.[42]

Aronoff, E. et al. (2016).Environmental enrichment therapy for autism: Outcomes with increased access.Neural Plasticity.[42]

Mendability Manifesto —Healing the Brain to Free the Person(2025)[18][17][19][31]

Mendability History — Claudie’s story and Sensory Enrichment Therapy development[23][25][37]

Interview with Claudie Gordon-Pomares (2020) — early enrichment successes[27]

[1][2][4]Autistic adults have an increased risk of suicidal behaviours, irrespective of trauma | University of Cambridge

[3][5]Traumatic experiences, psychological distress and suicide-related behaviours in autistic adults

https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/items/184e9b0f-5264-4225-96aa-eb99425ba209

[6][7][8][9]Is social camouflaging associated with anxiety and depression in autistic adults? | Molecular Autism

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13229-021-00421-1

[10]Understanding autistic burnout

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/professional-practice/autistic-burnout

[11][12]The Perceived Causal Relations Between Sensory Reactivity Differences and Anxiety Symptoms in Autistic Adults — PMC

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9648696/

[13][14][15]Post-traumatic stress disorder in autistic people

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/professional-practice/ptsd-autism

[16]Frontiers | Associations Between Cortisol Stress Levels and Autism Symptoms in People With Sensory and Intellectual Disabilities

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/education/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.540387/full

[17][18][19][20][21][22][29][30][31][38][39][40][41]Welcome to Mendability

[23][24][25][26][35][36][37]mendability.com

[27][28]Interview with the founder of Sensory Enrichment Therapy

https://mendability.com/post/interview-with-the-founder-of-sensory-enrichment-therapy