Did You Know You Can Influence the Development of Your Baby’s Brain While You’re Pregnant?

From the music you listen to, to the way you move, to the moments of peace you find—your experiences during pregnancy may already be laying the foundation for your baby’s brain.

Science is showing us that a baby’s brain development isn’t only guided by DNA. It’s shaped by experience...

...And this shaping begins earlier than we used to think.

A Rising Concern for New Mothers

The moment you find out you’re pregnant, your world shifts. Joy, love, anticipation, and sometimes, quiet worry. With the rising rates of autism (it's now 1 in 36 births in the US [1]), ADHD (now 1 in 10 births in the US [2]), sensory challenges, and learning differences, it’s only natural to wonder:

Is there anything I can do now to help my baby thrive later?

While no one can guarantee the prevention of neurodevelopmental conditions, there is growing evidence that the experiences you offer during pregnancy may support your baby’s brain in ways that make life easier down the road.

What if, during pregnancy, there were gentle, nurturing ways to support your baby’s brain as it grows?

What if the things you already do (taking a walk, listening to music, connecting emotionally) had a deeper impact than we ever realized?

What’s to lose in offering your baby a calmer, stronger, more adaptable foundation?

Identified prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) per 1,000 children in the U.S.

This isn’t about control or eliminating difference. It’s about giving every child a brain that feels safe, ready to learn, and capable of connection.

It’s about prevention, not perfection.

The Science of Possibility: Brain Plasticity and Environmental Enrichment

In neuroscience, there is a concept called environmental enrichment. Simply put, it explores how experiences shape brain development. This isn’t wishful thinking or pop psychology. It’s been demonstrated over decades, starting with rodent studies and now expanding to human applications.

In the 1960s, researchers found that rats raised in stimulating environments (with toys, social interaction, new sensory experiences, varied activities, etc.) developed thicker cortices, more synaptic connections, and improved learning skills compared to rats raised in standard lab cages [4,5]. Their brains literally grew more resilient, more capable.

This is the foundation of what we now call brain plasticity: the ability of the brain to adapt, grow, and rewire itself in response to experience.

And it’s not limited to childhood.

Brains are plastic throughout life—but they areespeciallysensitive during the early stages of development, including during pregnancy.

At Mendability, we’ve translated this science into Sensory Enrichment Therapy, designed for families. In randomized controlled trials with children on the autism spectrum, we saw measurable improvements in emotional regulation, communication, and learning. The children’s brains became more efficient at processing the world—and their lives became easier as a result.

So, what does this mean for babies who aren’t even born yet?

What We Know About Brain Development Before Birth

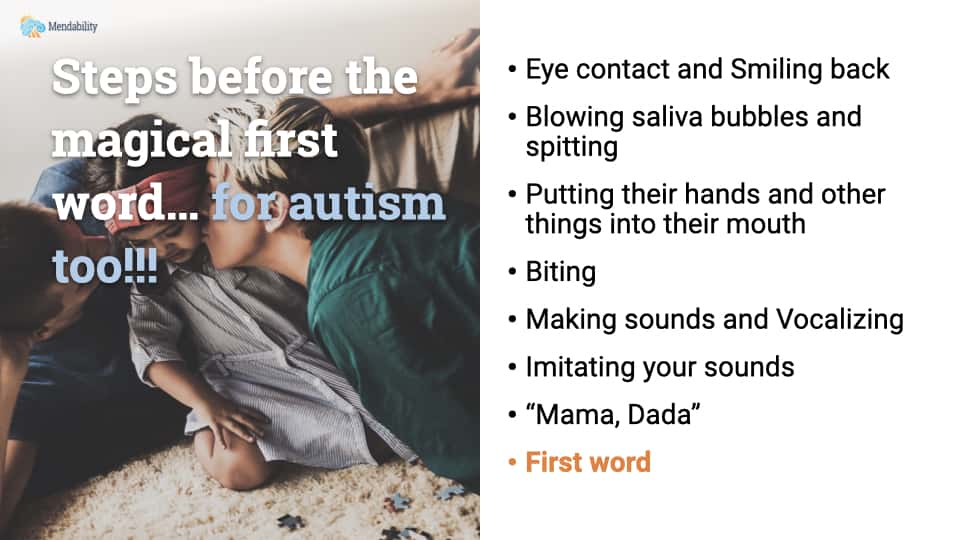

From as early as the second trimester, babies can begin to perceive sound. They become familiar with their mother’s voice, her heartbeat, the rhythms of her body. Later, they begin to respond to light, movement, even flavors through amniotic fluid.

Interestingly, smell and touch are the first senses to develop in the womb, an early clue to how essential they might be for organizing brain pathways, especially after birth.

Their developing brains are shaped not just by genetics, but by input—by experience.

Stress hormones, for example, can cross the placenta [8]. Chronic maternal stress has been linked to changes in fetal brain structure, emotional regulation, and even immune function [3].

On the other hand, nurturing experiences during pregnancy (soothing touch, joyful music, laughter, connection, etc) may offer protective and enriching effects on the brain of the baby.

For example, a recent study using 4D ultrasound showed that when a mother gently rubbed her abdomen, their fetuses increased their arm, head, and mouth movements. They did not feel the rub, but they felt the mother's response to her own rubbing.

4D illustrations of fetuses displaying arm, head, and mouth movements; the hands touching the body and the arms in crossed position.

In fact, the baby responded almost 2x as much to that than to hearing the mother's voice.

Average frequency of arm movements per minute including standard errors for all three conditions (‘Control’, ‘Voice’ and ‘Touch’).

Mechanisms Linking Maternal Enrichment to Fetal Development

Hormones

When a mother engages in relaxing or stimulating activities, it can influence the hormonal environment shared with the fetus.

These hormonal shifts, such as increases in oxytocin or reductions in cortisol, can influence fetal development at a cellular level. For example, lower maternal stress may support the growth of brain regions responsible for emotional regulation and memory.

On the other hand, hormones like serotonin and dopamine, associated with calm and pleasure, may also play a role in shaping how the developing brain wires its reward and stress systems.

In fact, a study showed that if you place pregnant rat moms in an enriched environment, their pups will handle stress much better than their counterparts with moms who live in a standard environment [6].

But, even more remarkable, the researchers found prenatal enrichment had 2X the anti-anxiety effect on the pups compared to placing the pups themselves in an enriched environment.

Human research is only starting to catch up, but they are finding similar results [7].

Epigenetic changes

Experiences during pregnancy may impact which genes are expressed in the developing brain. These changes are influenced by external or environmental factors, including stress levels, diet, exposure to toxins, and emotional experiences.

For example, studies have shown that maternal stress can activate or suppress genes related to emotional regulation, while nurturing environments may enhance the expression of genes that support cognitive and emotional resilience.

In this way, a mother's experiences don't just shape her own health. They may be "writing" instructions that influence how her baby's brain grows and functions.

Sensory priming

Repeated exposure to sounds, rhythms, and sensations may help wire early sensory systems for smoother processing. When the babies are born they are born with better tools to understand the world more quickly.

The fact that smell and touch are the first senses to develop in utero is not just a biological footnote. It may be nature’s way of prioritizing the systems most essential to early bonding and survival. After birth, touch and scent continue to play foundational roles in calming, feeding, attachment, and self-regulation.

These early sensory pathways create scaffolding for more complex brain functions like attention, language, and social connection.

What You Can Do: Gentle Protocols for Brain-Enriching Pregnancy

You don’t need a medical degree or a strict routine. Supporting your baby’s brain starts with supporting your own:

Create a Moments of Calm

Light a candle, dim the lights, play music you love. Your emotional state influences the baby’s environment. Choose moments of peace on purpose.Move With Rhythm

Walking, prenatal yoga, gentle swaying — all of these provide vestibular input to your body and, indirectly, to your baby. Rhythmic motion may help organize the developing brain.

Engage Your Senses

Take time to smell flowers, feel textures, enjoy flavors. These experiences uplift you — and that matters.

For example, spend a few minutes watching a slideshow of fine art, set to relaxing classical music. You can find examples here: https://mendability.com/sensory-enrichment-art-music-slideshowsBond Through Voice and Touch

Talk to your baby. Sing. Rub your belly lovingly. These gestures create connection and may begin to build neural pathways for trust and recognition.Protect Your Sleep and Emotional Health

Sensory processing and emotional regulation in your baby begin with your regulation. Get rest. Ask for support. Practice self-compassion.Limit Stress

Just like children, fetuses may benefit from predictability and moderation. Avoid chronic noise, overstimulation, or prolonged stress.

If you are interested in more more specific protocols, customized for you, schedule a free consultation here

After Birth: When Enrichment Might Be Even More Powerful

Once your baby is born, the window of opportunity becomes even wider.

This is when Sensory Enrichment Therapy shines. At Mendability, we’ve seen firsthand how adding hands-on, family-centered sensory activities can boost attention, communication, sleep, and emotional regulation in children — especially those diagnosed with autism.

In clinical trials, children who added Sensory Enrichment to their existing therapies were 6x more likely to improve significantly in their developmental scores. Many moved up an entire diagnostic category. And it didn’t take complicated equipment or intensive hours—just a few minutes a day, at home, with love.

Percentage of children with autism who improved by 5 points or more on the Childhood Autism Rating scale after 6 months

Percentage of autistic children who lost their ADOS diagnostic after 6 months

Imagine starting life with that kind of support.

Choosing Curiosity Over Fear

This article isn’t a promise or a prescription. It’s an invitation: to wonder, to explore, to participate.

You don’t need to fix your baby. You don’t need to be perfect.

But what if the way youfeelduring pregnancy matters more than you realized? What if your joy, your calm, your connection — became your baby’s first language of safety?

Science is just beginning to understand what mothers have always sensed: the bond begins before birth.

And there are things you can do to help that bond build a brain that is ready for life.

At Mendability, we believe that healing doesn’t happen in 45-minute sessions. It happens during play. During lullabies. During real life.

You’re not just growing a baby. You’re growing a brain. And we’re here to help you do it with confidence, compassion, and joy.

Notes

Rise in Neurodevelopmental Conditions in Children

Neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have become significantly more prevalent in recent decades. For example, in the United States the estimated prevalence of ASD in 8-year-old children rose from about 1 in 150 around the year 2000 to roughly 1 in 36 by 2020. Similarly, diagnosed ADHD in youth has increased markedly: one large nationwide survey found ADHD rates climbed from ~6% in the late 1990s to over 10% by 2015–2016. These statistics, reported by public health and research institutions, underscore a real rise (at least in identified cases) of neurodevelopmental conditions in recent years[1][2]. Multiple factors (improved awareness and diagnosis, environmental influences, etc.) may contribute, but the upward trend is well documented.

Maternal Stress and Fetal Brain Development

Maternal stress during pregnancy plays a crucial role in shaping the developing fetal brain, with long-term neurodevelopmental consequences for the child. A growing body of research links high prenatal stress or anxiety to alterations in fetal brain structure and function and to later cognitive, behavioral, or emotional challenges in offspring. For instance, elevated maternal distress is associated with differences in the infant’s brain growth and cortical development, as well as a higher risk of issues like poorer childhood self-regulation and behavioral problems. In one review of this literature, researchers conclude that prenatal exposure to maternal stress can have “enduring and wide-ranging” effects on the baby’s brain – affecting regions involved in learning, memory, and emotional regulation – and is linked to a spectrum of subsequent neurodevelopmental impairments in the child. These findings, observed in both human cohort studies and animal models, highlight that the intrauterine environment (particularly maternal psychological well-being) is a key early determinant of brain development and later neurodevelopmental health[3].

Environmental Enrichment in Animal Models

Foundational neuroscience experiments demonstrated that an enriched environment can improve brain structure and function in animals. In classic studies from the 1960s, groups of rats raised in enriched conditions (toys, social companions, and exploration opportunities) developed brains with thicker cortex, heavier overall brain weight, and greater synaptic connectivity compared to rats in standard or impoverished cages. Rosenzweig, Bennett, Diamond and colleagues were among the first to show that rats in a stimulating environment had measurably enhanced neuroanatomy – for example, a roughly 5% increase in cortical thickness and higher levels of certain brain enzymes, reflecting greater neuronal activity. Along with these anatomical changes came cognitive/behavioral benefits: enriched rats performed better on problem-solving and learning tasks than their impoverished counterparts, indicating improved memory and learning capacity. These landmark animal studies established that brain plasticity is strongly influenced by environment and experience. In other words, stimulating, resource-rich surroundings can spur better brain development and learning in animal models[4][5].

Prenatal Environmental Enrichment Buffers Stress Effects

Interestingly, providing an enriched environment during pregnancy can protect the developing offspring from some harmful effects of prenatal stress. A notable example is the study by Li et al. (2012): pregnant rats were exposed to chronic stress, and some were simultaneously given an enriched setting (larger cages with toys and enhanced sensory stimulation) during gestation. The pups from stressed mothers in the enriched condition showed markedly better outcomes than pups from stressed mothers in standard conditions. Specifically, prenatal enrichment prevented many of the stress-induced deficits – the offspring had reduced anxiety-like behavior and improved learning/memory performance in maze tests, nearly matching control (non-stressed) rats. At the neural level, enrichment during gestation preserved brain synaptic density and normalized levels of synaptophysin and glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus that would otherwise be disrupted by prenatal stress. In fact, just one week of maternal enrichment in late gestation was as effective as two weeks of postnatal enrichment after birth in improving offspring outcomes. This study provides proof-of-concept that prenatal environmental enrichment can mitigate the adverse neurodevelopmental effects of maternal stress on offspring[6]. It suggests that positive stimulation and reduced stress during pregnancy may act as a preventative “buffer,” promoting more resilient brain development even under challenging conditions.

Prenatal Stress-Reduction Interventions and Infant Outcomes

Emerging human research supports that helping mothers reduce stress or improve their well-being during pregnancy can positively influence the baby’s brain and developmental outcomes. A recent high-profile example is the IMPACT BCN randomized trial in Spain. In this trial, pregnant women at risk for high stress or poor nutrition were assigned to either a mindfulness-based stress reduction program, a Mediterranean diet intervention, or routine care. The children born to mothers in the intervention groups showed significantly better neurodevelopment at 2 years old compared to those in the control group. Notably, toddlers whose mothers participated in the stress-reduction (mindfulness) program had improved socio-emotional scores on the Bayley developmental scale, and those in the diet improvement group showed higher cognitive scores, relative to toddlers of mothers given standard prenatal care. In sum, structured lifestyle interventions during pregnancy – teaching mothers techniques to manage stress or providing nutritional support – yielded measurable gains in offspring cognitive and social-emotional development by age two. These findings echo smaller studies as well. For instance, another study found that infants whose high-stress mothers completed a mindfulness meditation program had more robust stress regulation at 6 months old (faster calm-down times and more self-soothing behaviors) compared to infants of mothers with no intervention[7]. While research in humans is still growing, such studies from reputable medical centers underscore that lowering maternal stress (through mindfulness, social support, healthy diet, etc.) can translate into developmental benefits for the baby. This is a promising and empowering message for expecting parents and healthcare providers.

Fetal Sensitivity to Maternal Signals

Far from being isolated, the fetus is exquisitely sensitive to cues from the mother and the external world. Maternal stress hormones are a prime example of biological signals that reach the fetus: the stress hormone cortisol can cross the placenta into the fetal circulation (though the placenta partially buffers it), especially when maternal levels are high or sustained. Researchers have shown that maternal and fetal cortisol levels tend to correlate, and excessive maternal cortisol is linked to changes in fetal growth and later infant stress reactivity[8]. Besides hormonal signals, fetuses also perceive external sensory stimuli. By the third trimester, fetuses can hear sounds and voices and even learn from them – for instance, studies have found that newborns recognize and prefer their mother’s voice (or even stories/songs repeatedly read aloud during pregnancy) compared to unfamiliar voices. In ultrasound observations, fetuses will respond with movements when the mother is speaking or when music is played near the belly. They also react to maternal touch: a recent study using 4D ultrasound showed that when a mother gently rubbed her abdomen, fetuses increased their arm, head, and mouth movements, indicating stimulation, whereas hearing the mother’s voice alone led to subtle calming (reduced movements). This suggests that an unborn baby can distinguish types of maternal interaction – they actively responded more to the mother’s touch than to her voice in utero. In short, the fetus is continually receiving chemical and sensory messages from the mother (stress hormones, sounds, vibrations, etc.) and can modify its behavior and physiology in response. These maternal signals provide the fetus with a kind of “preview” of the outside environment.

Mechanisms Linking Maternal Enrichment to Fetal Development

How might a positive maternal environment or enrichment during pregnancy translate into healthier brain development for the fetus? Scientists propose several interacting mechanisms: hormonal signaling, epigenetic modulation, and sensory neural stimulation. First, maternal stress hormones (like cortisol) are key messengers – lower stress and anxiety in the mother typically means lower cortisol levels reaching the fetus (due to both reduced production and the protective action of the placenta’s enzymes). With less exposure to high cortisol, the fetal brain may develop more optimally, since excessive cortisol can alter brain maturation and stress-response circuitry. Conversely, beneficial maternal hormones (such as certain growth factors or placental hormones) might be elevated in enriched conditions, supporting fetal brain growth[8]. Second, enrichment can alter epigenetic marks in fetal tissues. Epigenetics refers to chemical modifications on DNA or associated proteins that affect gene expression. Research has shown that maternal experiences can set epigenetic patterns in the placenta and fetus – for example, high maternal stress has been linked to increased DNA methylation of the fetal NR3C1 gene (which encodes the glucocorticoid receptor) in newborns, a change that was associated with heightened infant cortisol reactivity. By contrast, a mother who is less stressed or engaged in positive activities might foster a more favorable epigenetic profile (e.g. less methylation of stress-regulatory genes, or more expression of neurotrophic genes) in the developing baby’s brain. Such epigenetic changes could durably program the child’s stress physiology and cognitive development[9]. Finally, sensory priming provides a direct pathway: an enriched maternal environment often means the fetus is exposed to more varied sounds, rhythms, and even maternal movements. These sensory experiences can stimulate fetal neural circuits. Studies have demonstrated that fetuses can learn auditory patterns – for instance, repetitive musical melodies played during the third trimester lead to stronger brain responses in newborns, indicating a memory trace for those sounds. This kind of prenatal sensory enrichment might exercise and refine the fetal sensory pathways (auditory, vestibular, etc.), essentially “tuning” the developing brain. In summary, maternal enrichment likely affects the fetus through a combination of calmer neuroendocrine milieu, epigenetic tuning of gene expression, and direct neural activation from sensory experiences. All of these mechanisms are areas of active research, and they underscore the biological plausibility that a mother’s lifestyle and emotional state can influence her baby even before birth[8][9][10].

Early-Life Enrichment as a Therapeutic Tool in Autism

Early postnatal environmental enrichment has shown promise for improving outcomes in children with neurodevelopmental disorders like autism. In a pioneering clinical trial, Woo and Leon (2013) translated the animal enrichment paradigm into a home-based therapy for young children with autism spectrum disorder. They enrolled autistic children (ages 3–12) and had one group undergo a 6-month sensorimotor enrichment program at home in addition to standard care, while a control group received standard care alone. The enrichment involved daily exposure to a variety of sensory stimuli (e.g. tactile objects with different textures, scent jars for olfactory stimulation) and exercises engaging multiple senses together, aiming to stimulate the children’s sensory processing and brain plasticity. The results were encouraging: after 6 months, the enriched group showed greater improvements in cognitive performance and a significant reduction in autism symptom severity compared to the control group. In fact, 42% of children in the enrichment group had a clinically notable decrease in autism severity scores (on the CARS scale) versus only 7% of controls. IQ-related scores (visual reasoning on the Leiter scale) also improved more in the enriched children, by an average of +11 points over controls. Parents of the enriched children were more likely to report social and language gains as well. Follow-up work has similarly found that multi-sensory enrichment strategies can benefit children with autism, potentially by strengthening underused neural pathways and promoting adaptive plasticity in the developing brain[11]. While not a standalone cure, early environmental enrichment – in conjunction with behavioral therapies – is emerging as a valuable, low-risk intervention that can help improve cognitive and social functioning in children on the autism spectrum. This line of research, inspired by decades of animal studies, is a testament to how enriching experiences can be harnessed to support brain development in vulnerable populations.

References

Maenner, M.J., Shaw, K.A., Bakian, A.V., et al. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(2): 1–14. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Xu, G., Strathearn, L., Liu, B., Yang, B., & Bao, W. (2018). Twenty-year trends in diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among US children and adolescents, 1997–2016. JAMA Network Open, 1(4): e181471.

Wu, Y., De Asis-Cruz, J., Grundlehner, B., et al. (2024). Brain structural and functional outcomes in the offspring of women experiencing psychological distress during pregnancy. Molecular Psychiatry, 29(5): 2223–2240.

Bennett, E.L., Diamond, M.C., Krech, D., & Rosenzweig, M.R. (1964). Chemical and anatomical plasticity of brain: Changes in brain through experience demand, as seen in experiments with rats. Science, 146(3644): 610–619.

Krech, D., Rosenzweig, M.R., & Bennett, E.L. (1962). Relations between brain chemistry and problem-solving among rats raised in enriched and impoverished environments. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 55(6): 801–807.

Li, M., Wang, M., Ding, S., Li, C., & Luo, X. (2012). Environmental enrichment during gestation improves behavioral outcomes and synaptic plasticity in hippocampus of prenatal-stressed offspring rats. Acta Histochemica et Cytochemica, 45(3): 157–166.

Crovetto, F., Nakaki, A., Arranz, A., et al. (2023). Effect of a Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction during pregnancy on child neurodevelopment: A prespecified analysis of the IMPACT BCN randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 6(8): e2330255.

Gitau, R., Cameron, A., Fisk, N.M., & Glover, V. (1998). Fetal exposure to maternal cortisol. The Lancet, 352(9129): 707–708.

Oberlander, T.F., Weinberg, J., Papsdorf, M., Grunau, R.E., Misri, S., & Devlin, A.M. (2008). Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1), and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics, 3(2): 97–106.

Partanen, E., Kujala, T., Tervaniemi, M., & Huotilainen, M. (2013). Prenatal music exposure induces long-term neural effects. PLoS ONE, 8(10): e78946.

Woo, C.C. & Leon, M. (2013). Environmental enrichment as an effective treatment for autism: A randomized controlled trial. Behavioral Neuroscience, 127(4): 487–497.